Kastracijski stroji/English

| Castration Machines Theatre and Art in the Nineties Boris Pintar in Jana Pavlič |

| |||||||||||

Authors

Boris Pintar, a philosopher and a sociologist, is an author of essays and a writer. From 1992 to 1996 he was the manager of the international theatre and dance program at the Cankarjev Dom cultural centre in Ljubljana and a member of the artistic board of the Exodos contemporary performing arts festival in Ljubljana.

Jana Pavlič graduated in comparative literature and French at Ljubljana University. She works as a translator, essayist and dramaturg and leads Center for performance research DELAK in Ljubljana. Between 1995 and 1997 she was counselor for performing arts of the minister of culture of Slovenia.

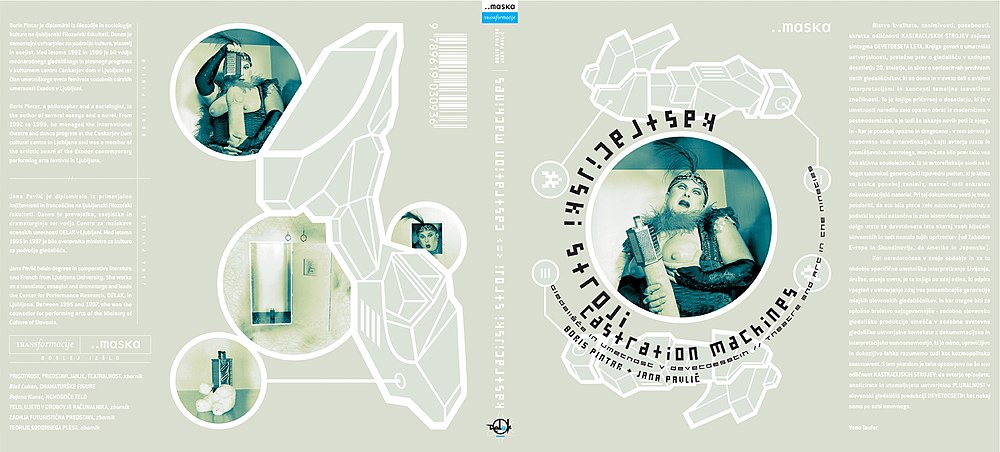

On the Cover

Ivo Godnič as hermaphrodite Lily in Ernst Toller's play Hinkemann, directed by Eduard Miler, staged by the Slovensko mladinsko gledališče (Theatre Mladinsko) in Ljubljana October 29th 1999, in a remake of Wilhelm Reich's orgon accumulator, costumes by Leo Kulaš, make-up Barbara Pavlin, photo Andrej Prijatelj, Ljubljana October 15th 2000

Design J.E.S.U.S. Ajaks, AJAX Studio

In 1784, Luigi Galvani discovered that electric current causes frogs' muscles to contract. Today, we know that the functioning of the muscles is controlled by weak electric impulses travelling from the brain via nerves. In 1864, James Clerk Maxwell developed a theory on electromagnetic waves, which represents the basis of radiophonics. In 1888, Heinrich Hertz discovered radio waves, a rapidly oscillating electromagnetic field, and, in 1895, Guglielm Marconi built the first radio receiver. In 1897, Nikola Tesla guided a ship by radio waves from a distance of several kilometers. The progress of science changes attitudes towards the body. The age of electricity saw the development of electronic manipulation of the body, making it possible to use electric impulses in the brain under the pretence of an accident. If electric impulses, shooting through the neurons while we are dreaming, are replaced by impulses of the encephalovideo, dreams can be transmitted to the sleeping. Dream interpreting psychoanalysis turns into a dream implanting psychosynthesis.

Max Weber’s fear that the rational bureaucratic organization, which places all power in the hands of the bureaucrats, might prove ineffective in times of crisis since bureaucrats are not qualified for initiative and decision-making and consequently operate in favour of the capital, turned out to be well-founded. While according to Weber the solution to the problem would be parliament and public control of bureaucratic organizations, the contemporary bureaucratic apparatus controls the public instead. Christopher Lasch's analysis of the narcissistic character of consumer society holds true primarily for its power elite. Social power is concentrated within bureaucratic organizations which function on the principle of secret services and indirectly maintain the dependence of more than half the population, thus turning democratic apparatuses into a soap opera. Centres of power organize the scientific elite, but their notions of Good and Evil are not subject to public reflection. The contemporary elite believes it has been chosen, and it believes in the sense-lessness of the people - the antithesis of the 18th century Enlightenment, which with its social reforms enabled the formation of the scientific elite. The contemporary elite no longer has an insight into the totality of the sociological, humanistic and technical sciences, unlike during the Enlightenment.

Despite all the splits, the Western world is governed by Christian regulation of sexual economy. Bourgeois morals seemingly place sexuality within the field of privacy in order to protect family values on the one hand and sexual fulfillment on the other. Deviant sexual practices remain conspiratory ‑ either sanctioned or privileged. When covert homosexuality or forced bisexuality is/becomes a measure of recruitment to top positions in secret organizations of power, the sexual orientation of the elite is no longer a private question but a political one. The culture of disclosure ‑ publicly parading the subconscious of individuals ‑ will also have to face the transparency of the elite's sexual orientation in order to preserve social consensus. The homosexual elite justifies itself as the ultimate possible system with a motto of ubiquitous bisexuality that further justifies public preservation of the heterosexual family as the basis of social reproduction as well as accelerating the secret expansion of homosexual prostitution. Covert homosexuality is approved by the heterosexual majority, by straight partners of homosexuals who consider it a success of the dominant socialization, and finally by the covert homosexuals themselves, who are rewarded with social respectability and privileges. Concentration of covert homosexuality within the structure of power has similar effects on society as irrational religious or nationalistic tendencies. An organization that posseses all the power functions cynically and clandestinely promotes conflicts that prevent the formation of a rival power. The result of such seemingly rational organization is massive bodily and intellectual prostitution, physical and psychological violence and the use of catastrophes as market stimuli. The covert homosexual elite justifies itself through hatred of the openly homosexual population, who are used as the subject in experiments on how heterosexuality is nothing more than the result of socialization and psychological development. Breaking homosexuals' limbs as a form of symbolic castration, and staged murders intended to evoke feelings of guilt, which aim to trigger the re-structuring of the subjects' unconscious fixation, remind us of the chairs used for torturing witches. Psychotherapy that is more interested in its share of the market than in social changes continues the tradition of religious wars. By propagating tragedies of the privileged, the yellow media maintain the social pact. The mechanism that could protect modern society from discrimination is the use of positive discrimination according to gender and sexual orientation when selecting cadres for the leading positions in the centres of power.

Art is a characteristic approach to the symptom: either as an unconscious circling around the symptom or as its conceptualization. In the first case, artistic form hides the symptom yet the symptom escapes in the form of symbols, in the role of women and in the form of inconceivable pain. In the second case, it answers the question of how to exist with the pain.

Boris Pintar

Translated by Mojca Krevel

I. Jana Pavlič: Prologue

[uredi]1. A Fragment of History

[uredi]Without a doubt, Slovenia represents one of the greatest theatrical mysteries of Europe. For big nations unacquainted with the autonomous governmental status of Yugoslavia’s federal republics[2], Slovenian theatrical art of the last eight decades has been veiled by the misleading front of the Yugoslav theatre. In the Hapsburg Monarchy that ruled the Slovenian territory for 600 years, Slovenian theatre was left to the sole care of Slovenians themselves – and of Viennese censors. The first and perhaps only major change that followed Slovenia's declaration of independence and the founding of the first independent Slovenian state in 1991, was external rather than internal in character: Slovenia and Slovenian art raised interest abroad. Despite dating back a thousand years, then, the term "Slovenian art" (and related notions such as that of "Slovenian theatre") only became international ten years ago.

Moreover, the West has generated its own image of the East - a cliché incongruent with actual reality. Aggravated by inaccurate geographical and historical knowledge, it has sprung from certain political manipulations, especially those of the big countries lulled by the comforting thought of belonging to grand nations - intangible and eternal monuments per se. Another cliché is that of isolation. Slovenia could hardly be defined as an isolated state, or one shielded from the influence of western mass and media cultures. From a geographical viewpoint alone, it represents a meeting-point of three European linguistic and cultural foundations - the Slavic, Germanic and Latin (and additionally borders Hungary). In the course of history, the Slovenian capital Ljubljana established itself as a multicultural centre, which is clearly reflected in the city’s architecture; it intertwines the Italian and German Baroque, the Austrian Biedermeier, and the Slavic variant of the Jugendstil and the Secession. In the 1920s and 30s, this natural openness was transformed due to the rise of Nazism in Germany and Austria, and that of Italian Fascism. Bordering Italy and Austria, Slovenia was fiercely exposed to this problem, and took to the process naturally initiated after the Spring of Nations: it leaned upon its Slavic neighbours in the Balkan south, and spiritually upon the Slavic world in general.

As one of the most important centres of the Noricum province, Emona (the Roman name for Ljubljana) probably had its own amphitheatre. The history of Slovenian theatre is closely linked to that of Slovenian literature and drama. The beginnings of Slovenian literature go back to the end of the 10th century - to the Freising Manuscripts, the oldest preserved writings in the Slovenian language. From the Middle Ages till the start of the Baroque period, four different languages were used on the territory of today's Slovenia - Slovenian, Latin, Italian and German. At the end of the Baroque, Latin ceased to be used as a public language, with the other three remaining till the end of World War One when Italian and German were replaced by Serbo-Croatian, only to return in World War Two. Slovenian thus acquired the status of exclusive official (and theatrical) language as late as after World War Two. The earliest elements of stage expression on Slovenian territory can be found in Christian liturgy - in Latin liturgical dramas of the 15th century. Performance in Slovenian, however, began at a much earlier date - in various forms of folk farce. The 17th century saw the emergence of the first German and Italian troupes (both travelling and residential), especially those of Italian opera singers. The Slovenian language first appeared on stage in Jesuit plays of the 17th century, which already combined secular and religious themes; the role of the devil, for instance, was often incorporated in the vernacular Pavliha character - the Slovenian equivalent of Scaramouche, Harlequin, or Hanswurst. In the same period, the Capuchin fraternity Redemptoris mundi was founded; boasting magnificent direction, acting, scenery and costumes, their performances - or rather processions ‑ depicted the Way of the Cross and other Biblical subjects. The third essential religious genre of the Slovenian Baroque theatre was the passion play. The most important are the Carinthian passions, and The Slovenian Passion (1721) by Friar Romuald (+ 1748), also known as The Škofja Loka Passion, after the town of Škofja Loka where it was staged. It required more than 300 performers, with the text comprising 1,000 Slovenian verses, several German passages, and instructions for direction. The theatre world of the Baroque was also marked by folk improvisation, traditional medieval religious plays, Jesuit school theatre, Italian opera, and the beginnings of German bürgerliches Trauerspiel (domestic tragedy). Jesuit plays and Capuchin processions, including The Škofja Loka Passion, were performed until 1773, when Empress Maria Theresa officially forbade their staging, allegedly because they caused too much disturbance among the population.

The course of Slovenian drama takes a historic turn at the end of the 18th century, when the spirit of the time was inspired by a circle of cosmopolitan intellectuals, advocates of Enlightenment thought and the French Revolution. They gathered around the famous historical figure, Baron Žiga Zois (1747 - 1819), the richest Slovenian of that period as well as a great mentor and patron of explorers and literati, including the playwright Anton Tomaž Linhart (1756 - 1795). Under Zois's progressive influence, A.T. Linhart wrote This Happy Day or Matiček is Getting Married (1790), modelled after La folle journée ou le Mariage de Figaro by Beaumarchais. Censorship prevented the work from being publicly staged, and the comedy saw its premiere as late as after the March Revolution in 1849. As opposed to most Slovenian dramatic texts that followed, Matiček excels in the delightful wittiness of the elegant, elaborate utterances of its protagonists, who also represent a wide range of social strata, from high nobility to simple farmers. As a cosmopolitan and an advocate of Enlightenment ideas, A.T. Linhart was highly-familiar with a variety of theatre praxes. Influenced by the Sturm und Drang, he also wrote Miss Jenny Love (1780) - a bizarre Shakespearean tragedy in the German language, and another comedy, The Mayor’s Daughter (1789).

In the early 19th century, Romance gaiety was smothered by Germanic oppression. Strict censorship was introduced by Metternich's absolutism, and Slovenian became a language less welcome in public life than it had ever been before. The oppressive atmosphere could not even be lightened by the brief enthusiasm over the Illyrian Provinces (1809 - 1813) and the French authorities that supported the wish for Slovenian autonomy. Such conditions gave rise to subtle, introverted Romantic poetry, especially that of Dr. France Prešeren (1800 - 1849). Despite continuously promising a great tragedy, the greatest Slovenian poet never wrote one. The Romantic theatrical scene generally consisted of German troupes offering a classic repertoire (Lessing, Schiller, Goethe, Shakespeare, Molière, Goldoni). In addition to the cessation of Italian influence, the French retreat was also followed by the disappearance of Slovenian theatrical creativity. Theatrical activities became somewhat more lively after the March Revolution, but were again suppressed by Bach's absolutism. In fact, the Slovenian theatre began to rise again as late as after the introduction of the constitutional monarchy - more precisely, with the foundation of the Ljubljana Drama Society in 1867. Also of considerable importance was the Slovenian Drama Society in Trieste, which performed in a number of Trieste theatre houses. The Fenice Theatre, for instance, recorded almost 2,000 Slovenian visitors to their productions during the 1889 season.

Slovenian theatre and drama returned in full bloom after 1892, when the Ljubljana Drama Society acquired a new building - the Regional Theatre, and the dramatist Ivan Cankar (1876 - 1918) appeared. Until the erection of Kaiser Franz Joseph Jubilaums Theater (Emperor Franz Joseph’s Jubilee Theatre) in 1911, the stage of the Regional Theatre was shared by both Slovenian and German ensembles. Lasting until the end of World War One, the time of Cankar's artistic creativity is also referred to as the Cankar Period. Cankar was the first to overcome the theatrical passivity of the 19th century, generated by fear for the Slovenian nation and its language in the captivity of the Hapsburg Monarchy, the "dungeon of nations". Like his novels, short stories and sketches, his dramas are superb literary works, dealing with the problems of art and its maker at the turn of the century; at the thought of the world being abandoned by God, the artist is filled by a mixture of delight and horror, interpreting the outbreak of World War One as a dark omen ‑ Minerva’s owl setting out at twilight. His dramatic work marks the beginning of a proper, integrated theatrical art after the void of the 19th century. The significance of Cankar also lies in the fact that he initiated the search for different staging concepts; from their premieres onwards, his dramas imposed great directional challenges.

After the end of World War One, which saw the founding of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, professional Slovenian theatre houses were named Slovenian national theatres and also started their own theatre schools. The most important Slovenian theatre centres were Trieste, Ljubljana and Maribor. In the first half of the 20th century, the development of Slovenian acting was primarily influenced by two leading actresses of the stage - the Slovenian Marija Vera (1881 - 1954) and the Russian Marija Nablocka (1890 - 1969). The former was a professor of artistic speech at the Ljubljana acting academy, AGRFT, and the first Slovenian theatre directress. Having received her education in the German school of acting, she co-operated with Max Reinhard and performed on all the eminent European stages with renowned actors of that time (e. g. Joseph Kainz, and Alexander Moissi in St. Petersburg). The latter came from the Soviet Union in the early twenties, and brought the experience of Russian and Soviet theatres, as well as the acting style of the MHAT. The most notable directors of that time were Osip Šest (1893 - 1962), Bratko Kreft (1905 - 1996), Ferdinand Delak (1906 - 1968), and Bojan Stupica (1910 - 1970). They were initiators of director’s theatre, and authors of prominent theoretical texts on theatre art and direction. The most important was Ferdinand Delak. His directional approach was based on elaborate auto-poetics reflecting the historical avant-gardes of Constructivism, Futurism and Bauhaus. Having travelled in Europe (Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Prague) from 1927 till 1933, he created his most important works in the 1930s as artistic director of The Worker's Stage in Ljubljana, an independent theatre company, which also produced notable performances of modern dance theatre - a genre which influenced the stratification of Slovenian stage arts.

2. New Times - New Systems

[uredi]After the Second World War, the aesthetics of the Slovenian theatre soon split into those of the national theatres and of their antipodes - small theatres devoted to theatrical experimentation. The latter dealt with new variants of dramatic theatre generated by the young generation of playwrights or with modern stage expression without words - as influenced by Brecht, Grotowski, Living Theatre, Brook, non-European theatre, new readings of Artaud, Craig, Meyerhold, Appia, and Stanislavsky.

The most stirring periods were the 1960s and 1970s, with experimental aesthetics entering national theatres as enforced by the new generation of directors. This movement’s most important member was Mile Korun (1928 -), who embodied a clearly modernist theatre conceptualism. He was the first Slovenian to face the challenge of contemporary Anglo-American as well as European dramatic texts, and also sought to reinterpret the classical and Slovenian authors. One of his most important stagings was that of Cankar's The Scandal in St. Florian's Valley (1965), with its influence reaching far into the 1980s.

In the meantime, small independent stages continued to explore the latest trends –theatre happenings, ritual theatre, theatre of cruelty, theatre of panic, physical theatre. Perhaps due to its strong connection to contemporary drama, the most significant experimental theatre company was the Stage 57 (1957 - 1964), which during the seven years of its existence staged as many as 13 premieres of works by young Slovenian dramatists, the most prominent being Gregor Strniša (1930 - 1987), Dane Zajc (1929 -), Dominik Smole (1929 - 1992), Primož Kozak (1929 - 1981) and Vitomil Zupan (1914 - 1987). They were soon joined by the members of the youngest generation active on other small stages - Dušan Jovanović (1939 -), Ivo Svetina (1948 -), Milan Jesih (1950 -), Emil Filipčič (1951 -) - most of them renowned poets as well. Influenced by Sartre, Beckett, Anouilh, Ionesco and Anglo-American playwrights of the 1960s and 1970s, they produced important dramas intertwining nihilism, existentialism, the absurd, and ludism. The most characteristic dramatic form of that time was poetical drama – a specific product of Slovenian literary modernism.

The end of the 1960s saw the rise of another powerful generation of theatre directors; having begun their creative work unrecognized by established institutions, they soon entered them and introduced radical changes. The most important were Ljubiša Ristić (1947 -), Meta Hočevar (1942 -), Janez Pipan (1956 -), and the director and playwright Dušan Jovanović (1939 -); active in the Mladinsko Theatre at the end of the 1970s, they established the foundation for the experimental polygon of new theatrical forms. Based on the fatal encounter of politics and art, their performances as well as their concept of organization focussed on the relationship between polis and theatre.

In the second half of the 1980s, theatre institutions were stormed by the brilliant works of three young directors: Dragan Živadinov’s The Baptism under Triglav (1986), Vito Taufer’s Alice in Wonderland (1986), and Tomaž Pandur’s Sheherezade (1989). Following the modernist school of Mile Korun, the praxis of political theatre as enforced by the Mladinsko Theatre, and their own singular interpretations of the basic dramatic works of the 20th century, the theatrical individualism of the three directors exerted a decisive influence throughout the nineties.

In the 1980s, Ljubljana was deafened by a cultural explosion. "The last Moscow metro station", as defined by some, changed from a small provincial town into a capital of alternative and subcultures, giving shelter to the marginal, the wronged, the ostracised. The eternal spirit of revolution sparked a confrontation with the state – a fight for one’s own rights and, romantically, for those of the nameless and demeaned. By committed actions for the installment of civil society, Slovenian punk, gay[3], and other "outraging" movements forcibly obtained their own space in the drowsy province traditionally intimidated by everything unusual, eccentric, or connected with unofficial interpretations of art and culture.[4]

In the whirlpool of creative passion, the theatre acted like a grand conqueror of grand stages, and even ceased to consider itself theatre. Directors proclaimed themselves constructors of a united art - innovators with their stages shifting from theatre halls to the state itself. How should the state be conquered, and transmuted into an artistic one? they ask. By evoking great utopians like Meyerhold, Tairov, Craig, Appia, and Artaud, the theatre declared itself a utopia capable of changing the world and the state -- a concept powerful enough to place Slovenia onto the map of Europe, and make Ljubljana a capital of culture; one able to fascinate, seduce, and conquer. The new art was created by the generation born in the early sixties, as the art of the seventies had been made by the fifties generation. The buzz-words of the day included provocation, demolition of the established order, of the institution and the state; manifestos, concepts, new Slovenian art, new Acropolis, new Europe, and new Slovenia. The year 1990 indeed saw the transformation of the state.

Ljubljana became an important cultural centre, with the euphoria of the eighties continuing into the next decade. In the theatre, the explosion of aesthetics, strategies and artistic tactics was in full sway. There were great themes, and great stories: Dr. Faustus, Divina commedia, prayer machines, and confrontations of the artist with the state. Searching for new possibilities were Tomaž Pandur, Dragan Živadinov, Vito Taufer, Marko Peljhan, Emil Hrvatin, Vlado Repnik, Bojan Jablanovec, Matjaž Berger, Matjaž Pograjc - all students of the Academy for Theatre, Radio, Film and Television (AGRFT),[5] the only Slovenian institution of this kind. In less than a decade, the eighties generation radically transformed the Slovenian theatre system and tackled the established conventions of that time, offering new interpretations, forms and models. Theatre art opened to explore its borders, internal laws, and connections with philosophy and high technology. It focussed on the body as well as on the new principles of dramaturgy, direction, and montage that emerged at the end of the century, culminating in zero gravity theatre - in the real cosmos.

Despite its aesthetic diversity, the art of that period did not gain support in terms of organization and finance. Despite the scarcity of financial aid, magnificent, technically demanding projects were realised, with their authors compelled to seek international recognition and battle with the state. The superhuman efforts, however, took their toll. The mid-nineties saw the collapse, or rather, the destruction of the titanic era, which could also be viewed as a general symptom of the global prevalence of a neo-liberal capitalist mentality. Political scheming[6] and selfish interests hampered those heading state institutions; independent production, however, retired into intimacy after wasting too much of its creative energy in bureaucratic strongholds, fighting for recognition and financial means.

Since the early 1980s, Ljubljana has been considering building a Centre for Contemporary Art to fill the gap in the cultural infrastructure and provide highly professional work to all artists uninterested in or hindered from entering the theatrical institutions of the state and developing individualist aesthetics, strategies and praxes.

The Slovenian system of theatre organization was inherited from Austria-Hungary with regional theatres (Landstheater). Since 1945, when they began to be almost exclusively financed by the state and confirmed the aesthetic principles and art theatre of Stanislavsky, Slovenian theatres have seen no major changes, except a growth in number. After 1945, two professional repertoire dramatic theatres with permanent ensembles and staff (in Ljubljana and Maribor) were joined by others, for a total of ten nationwide, and one in Trieste sponsored by the Italian government; two of them are dedicated to puppets, concentrating almost exclusively on young audiences; and two operas and ballets. As state institutions, all these theatres are part of a firmly established and quite obsolete system governing the so-called public “cultural institutions”. Their theatre programmes consist exclusively of their own productions, reaching an average of six premieres per season - the quantity necessary to guarantee the support of the Ministry of Culture.

An exception is the Mladinsko Theatre, one of the aforementioned ten state theatres, which managed to achieve the unofficial status of non-repertory theatre (and not exclusively for drama), following its own specific artistic course from the end of the 1970s. Within a chaotic system, it attempts to chart its own artistic path, seeking to enable unconventional directors to carry out their research with the aid of an acting ensemble ready to face a variety of challenges. Thus, by the mid-nineties, the Mladinsko Theatre realized several productions that would not have been possible anywhere else. In the creative space of the Mladinsko, the aforementioned directors have recently been joined by younger colleagues who, by means of individualistic artistic methods, explore the as yet undiscovered theatrical horizon reaching from pure drama to total abstraction. For the last twenty years, Cankarjev dom, a Cultural and Congress Centre - a vast public institution chiefly of the distributional type - has helped to fill the lack of a suitable production structure for contemporary stage art by producing research projects that venture beyond classic theatre into new technologies and territories of hybrid, non-mimetic scene events. In the thirty years of its existence, a small private theatrical structure, the Glej Theatre, established itself as a nexus for the most unconventional, non-theatrical young authors. In the 1990s, it was transformed into a space for theatrical research taken over by individualist members of the seventies generation without artistic restraints. Fascinated by pop-culture, they create performances, sometimes verging on amateurism, that reflect the spirit of new urban anthropological phenomena. Sociologically speaking, their work may best depict the atmosphere of "fin de siecle". Taking a slight distance, they play with the image of a new "lost generation".

The new legal regulation of culture enforced in 1994 provides an opportunity for state and private cultural structures acting in the public interest to gain equal status, but the law remains ignored by the cultural politics enforced by the Ministry of Culture. Thus, the status of private theatrical institutions has seen virtually no changes since their emergence in the early 1980s. The state and local communities still favour the institutions they themselves founded, and are unable to initiate suitable action for a reform that would also dispense with the very outdated cultural politics of the state itself, which assigns independent artists marginal positions, and perceives new independent structures as suspicious. At the same time, it threatens a reckless reform of state theatre institutions by dispensing with regularly employed administration staff - thus offering an alternative of Scylla and Charybdis.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Slovenian theatre has been split into two parallel worlds: the official, legitimate plane of the theatrical institution, and that of rebellious iconoclasts demanding new forms and systems. It generally takes about 20 years for the latter to force their way into the institution - to be themselves targeted as they mature.

We could also not talk of a national distribution network in Slovenia. With non-drama theatre forms virtually non-existent, or at least extremely rare till the nineteen eighties, the old distribution network of national theatres which (at least superficially) met all demands so far, proved entirely inappropriate when experimentation become the predominant theatrical expression of the next decade. Moreover, the Yugoslavian festival network, along with its openness that helped cover the drawbacks of local distribution, no longer existed.

The 1990s gave rise to a generation of young directors (Janežič, Horvat, Novakovič) relying on tactics different than those of their forerunners in the 1980s. It is likely that the fate of their older colleagues who, inspired by the idea of eternal revolution, wished to change the world, but remained stuck in the rigidity of the system, led them to make use of intimate strategies. Their work appears more secretive, slow-paced and distant, and their art introverted and fairly shy. We thus witness the co-existence of two strikingly different generations - those of the 1980s and the 1990s - who share the same marginal position with regard to the privileged institution, a state of affairs generating tension and conflict. The situation is forever on the brink of crisis. The pathological narcissism of the new governing structures in power alienates them from art with content. The prevailing neoliberal strains result in garish images without content - cosmetics covering the actual situation. The danger for art does not arise from the omnipresence of populist trends, but from the absence of cultural politics, and from the refusal of public officials to take responsibility and interfere, intimidated as they are by the negative experience of one-party monotheism, which totally abused its right to exert influence upon any sphere.

The consequences are not entirely tragic, as yet, but there is a sense of foreboding in the air. There must be some kind of short circuit present between the author and the user or agent. Similarly, the high concentration and quality of new, non-dramatic forms of stage art, haunting Slovenian culture as a kind of unwelcome phantasm, is not very far from the symptom sensed by Ivan Cankar at the beginning of the 20th century: searching for affirmation in his home ground, the Slovenian artist will tragically slip under, suffocated by alienation trauma. In theatre, the most ephemeral of arts, this outcome becomes even more probable, as posthumous recognition is not to be expected.

Translated by Urška Zajec

II. Boris Pintar: Castration Machines

[uredi]Abstract

The following text analyzes the pretension of some contemporary theatre events to function as symbolic castration machines. The dispute regarding symbolic castration - the Oedipus complex - reached its culmination in the 1970s. One side claimed that pathological narcissism and pan-sexuality were a consequence of the permissiveness of the consumer society, since genital sexuality is a result of the consequence of the solved Oedipus complex in the process of socialization (Lacan, Lasch). The other side defended the position that the desire to create is not merely oedipal and that normality is a variable notion of the social contract, where truth is still bound to power (Deleuze, Guattari, Foucault). Institutions of power empirically confirmed the oedipal hypothesis, although the real experimental proof of the notion that regressive sexuality is in fact a consequence of a disavowed castration in childhood would be the symbolic castration of an adult. Using three theatre events, we will demonstrate how theatre can function as a castration machine, the logic of which is connected to the logic of the chair for torturing witches to confess to witchcraft.

The Science of Sexus

With Freud's 1899 study The Interpretation of Dreams (Traumdeutung), sexuality steps into the center of scientific interest in the 20th century – the aim is to verbalize, explain and analyze pleasure people have been indulging in for millennia, without really knowing why. Before the Second World War, psychoanalysis went in many different directions. Reich, for example, who with his program of sexual liberation of the working class later influenced the sexual revolution in the sixties, spoke in favor of sexual liberation. He designed the accumulator of orgone energy - the cosmological sexual energy, a huge metal box into which a patient was put. Energy transmitted into the patient reestablished capability for orgasms, lost due to neurosis. Fear of Nazism brought him to the United States where his production of orgone accumulators and therapy landed him in prison in 1957. He died in prison soon afterwards and his orgone accumulators were destroyed. Others, Lacan among them, established that sexual fulfillment is imaginary since the reproductive function denies pleasure to the subject. Reich inspired mass movements, whereas Lacan inspired exclusive organizations.

One of the more enigmatic problems of sexuality is homosexuality, which before becoming a subject of scientific research was tolerated in more or less covert forms and social roles. Scientific treatment pushed it into pathology where, if nothing else, it had to at least be explained. The search for a solution to the enigma of the origin of sexual inclination puts psychology and genetics into competition, the two fields meeting in combined theories until a final solution is reached. Freudian psychoanalysis considers homosexuality a consequence of the unsolved Oedipus complex, the disavowing of symbolic castration, which is, with permissiveness, becoming the prevalent model of socialization in post-industrial society. Our aim is to show how the theatre boxes into which the spectators or the actors are put function as castration machines.

On the Ambivalence of the Elites

The stigmatizing of a certain behavior stimulates its conspiratorial organization, the perversity of which may become linearly proportional to public indignation, and covert homosexuality to patriarchal machismo.[8] Homosexuals organize themselves as a threatened group, thus enabling the establishment of an invisible homosexual elite with considerable influence upon life in society. In European metropolises, homosexual sub-culture emerged during the two world wars, first in artistic and entertainment circles where acquisition of the behavior of the opposite sex was tolerated for the production of comical effects. But the Second World War put an end to the socialization of homosexuals as a social group, and Nazism placed homosexuals at the bottom of the scale of social degenerates, despite the fact that homosexuality was present among the highest Nazi leaders. "That was why they [the Nazi elite] cherished everything that could protect them from relating to women and sensuality: "German nation, fatherland, native soil, home village, home town; the jacket (uniform); other men (comrades, superiors, lower ranks); military unit, community, blood-ties; arms, hunting, combat; animals (especially horses)."[9]

After the war, homosexuals did not receive the same rehabilitation as the rest of the oppressed. At the end of the 20th century, however, the homosexual way of living is increasingly gaining the status of an acceptable form of Western family life. Anthropologists discovered the same phenomenon in some primitive societies and among American Indians, where a male homosexual could assume the female role in society and live with another man. In Ancient Greece, socially distinguished homosexuality was not a form of family life, but an erotic bond between an older male teacher and a boy-student. Such relations were prescribed; relationships between boys were prohibited, as was female homosexuality, since the social role of women was to take care of the family.

The relationship of the homosexual elite towards homosexuality is ambivalent: on one hand, it uses its influence to support the tolerance of homosexuality and homosexuals (visible, semi-visible and invisible) in society, which is typical of all communities of interest; but on the other hand, such free choice would undermine the reason for its organizing and its privileges.[10] Heterosexual socialization provides invisibility for the homosexual elite and for that reason the homosexual elite cooperates in the heterosexual socialization of homosexuals. Cases of violence against homosexuals are not just restricted to violence inflicted by the heterosexual majority upon the homosexual minority, but also include the violence of homosexuals, who are – visible or invisible - present at all the levels of social stratification. Let us illustrate this relationship with an allegory: if AIDS was an invented word, homosexuals would have invented it.

The modern elite is becoming more and more sophisticated and highly educated, which is the reason for their feeling of superiority over a population with only an average education. The latter are becoming an object of the modern elite's consumption, leisure and study. But at the same time, the elite is becoming more and more unfit for social action, expressing its helplessness in a formula of spontaneity that, it suggests, will resolve today's social problems. Solving problems is a matter of individual environments; the most drastic example is the production of generations that are going to die out, which is how the environments that produced the world's elite gained their prosperity. Universal acquisitions may seem spontaneous to the members of the elite, who never had to take a risk in order to occupy their positions, but the rise of cowards without compassion within the modern elite could ruin the culture. We expect the elite to be capable of brave action, not just of risking the lives of those who are nothing more to the elite than objects of their experiments.

Theory of Pathological Narcissism

American historian and sociologist Christopher Lasch claims that pathological narcissism is the nature of postindustrial society. Lasch enumerates the following chief characteristics of a pathological narcissus: addiction to the unselfish warmth of others, together with fear of that addiction; manipulation with impressions he makes on people he despises; calculated seductiveness; inability to live without an audience that admires him; hunger for self-cognition; nervousness; self-deprecating humor; lack of interest in worldly matters; feelings of emptiness and suppressed rage; and fear of competition. Also typical are an inability to mourn; a possibly unsatisfied oral desire; promiscuity and pansexuality; fear of the castrating mother; dread of old age and death; hypochondria; changed perception of time; obsession with celebrities; loss of spirit of playfulness; and a somewhat poor relationship with the opposite sex.[11]

In his analysis of pathological narcissism, Slavoj Žižek follows the path of Lasch and Lacan: "The basic element of pathological narcissism is a failed integration of Law, represented by the Name-of-the-Father, the fatherly Ego-Ideal, a failed symbolic identification with the Ego-Ideal (which is a result of a "normally" solved Oedipus complex), the replacement of the paternal Ego-Ideal with a pre-Oedipal "sado-masochistic", "anal", "maternal" superego."[12]

A few pages later, Žižek writes: "Lasch's greatest merit is in showing that the cult of "authenticity", the cult of free development of the "great Ego", free of "masks" and "repressive" rules is nothing but a form of its opposite, the pre-Oedipal addiction, and that the only way out of this addiction is through identification with a certain de-center, foreign, to the Ego external instance of the symbolic Law."[13]

Heading Towards the Oedipus Complex – "For those who believe in the Oedipus complex only"[14]

According to Freud, homosexuality and fetishism are a consequence of the unvanquished threat of castration.[15] For Lacan, symbolic castration – Oedipus ‑ is the signifier-master that bars the subject, introduces sexual difference within the symbolic, separates the normal from the pathologic, good from evil.[16] "What analytic experience shows is that, in any case, it is castration that governs desire, whether in the normal or the abnormal."[17] Genitality as a result of the development of child's sexual stadia – oral, anal, phallic, Oedipus complex and latent – does not exist in itself; there are only approximations of Genitality as a consequence of the authoritative Oedipus, totaling the pre-Oedipus polymorph perversity, submitting it to the reproductive function. "Psychoanalysis makes the whole achievement of happiness turn on the genital act."[18] The disavowal of symbolic castration means being cut off from reality. The symptoms of a disavowed castration are correlative to a pathological narcissus: not renouncing one’s own penis as the central organ of narcissistic satisfaction; fear of castration expressed in the obsessive repetition of actions that symbolize castration; accumulation of castrating objects; fetishism of substitutes for the phallus, gaze, voice, movements, sounds, light. "The subject is trying to preserve the phallus of the mother."[19]

In the seventies, the fundamentalism of the psychoanalytical Oedipus was juxtaposed with Deleuze and Guattari's schizo-analysis. "The problem of the socius has always been to encode the fluxes of desire, to inscribe them, to register them, to make sure that no unblocked, unchanneled and unregulated fluxes are flowing."[20]

And they continue: "It is certain that partial objects contain a charge sufficient to blow Oedipus apart and rid it of the stupid pretension that it represents the unconscious, that it triangularly frames the unconscious, that it subordinates the entire desiring production. The question that we may ask in this regard is not the one about the relative importance of what we could call the pre-Oedipus in relation to Oedipus (since the "pre-Oedipus" is still in evolutionary or structural reference to Oedipus). We are talking about a question of the absolute non-Oedipus character of the desiring production."[21]

And conclude with: "The evil has been done, therapy chose to follow the path of Oedipization ‑ all clogged with waste ‑ against schizophrenization that has to heal us from therapy."[22]

Operation of Castration Machines

Symbolic castration is an unconscious operation, whereas associations are the instrument for managing the unconscious. The theatre, with its archaic and vivid relationship between actors and spectators creates more suggestive pictures with a deeper range of memory than film where the flux of events is not interactive. Theatre boxes are machines that with different effects produce the flux of energies evoking in the subject unconscious states, events, and perceptions, while the subject's conscious attention is directed in fascination towards the performance.

"The question to be or not to be phallus, and to have to be phallus without having one - that is how I define the feminine position."[23]

The Course of Falsification of the Analysis

In the first stage, the subject supposedly needing castration (SSC) is brought to the state of love by means of subjects that conform to the Ideal-Ego of the SSC. The object of love acquires the function of the analyst and enables transference, the materialization of the reality of the unconscious - sexual reality. While transference is a means of closing the unconscious, paradoxically, the analyst has to wait for the transference before beginning interpretation.[24] In the second stage, the SSC, who can be a spectator, a performer, a director etc., is put within an environment which engenders castration associations on multiple levels, from direct to transmitted. In this stage, the SSC is subjected to childhood memories, memories of situations possibly responsible for the disavowal of castration and with the symptoms of concealment. By gradually increasing the load, we enfeeble the SSC's defense mechanisms. In the third stage, we stimulate the SSC to analyze himself by means of artificially triggered paranoia, which are enhanced by revealing the objective. The SSC is trapped within a state of narcissistic paranoia, which is the last stage before passage (la passe) – castration. In this stage, the object of the SSC's love rejects the SSC and triggers the destruction of his imaginary world. Projection is followed by introjection and the rise of the symbolic. If not, the fiasco is turned into a joke, made a consequence of the nature of the world. We face the SSC with our limitless superiority and passion for repetition. We give him back a part of his narcissism by incorporating him into the analysis of others. The operation is repeated until success is achieved. Such interruptions of the natural state disturb the perpetuation of the network psychology despite highly developed technology.

"Probably the most interesting and for the Slovene space most specific inhabiting of the space is the creation of parallel "theatre" worlds. "Conceptual constructs" deciding for the "topical" or "optical" principle (Emil Hrvatin) are on one hand a result of Messianism, and on the other hand a utopian project of the post-avant-garde artists for whom their work is not only a mission, but also a test field where the belief of those performing and the perceptive (un)adjustment of the audience are tested."[25]

Architectural constructs and playing with the spectator's view in Dragan Živadinov's theatre events can be understood as a castration machine. In his Drama Observatory Zenit (Ljubljana, 1988), performed inside a railway wagon with a rocket installed in place of the ceiling, the spectators stood at the sides of the wagon. Along the performing space in the middle of the wagon, at the height of their heads, an altar of St. Mary moved on the tracks - a castrating mother associated with decapitation. In this performance, the mimetically luxurious set decoration[26] was based on the homely kitsch that created the space of the cathedral (it was a performance of Eliot's Murder in the Cathedral) in a Slovene kitchen and cowshed. More illustrative symbols of castration can also be found in other Živadinov's performances playing with the spectator's view; in Marija Nablocka (Ljubljana, 1985), the heads of the spectators were caught into the performing surface of the stage upon which the actors moved and put their hands over spectators' eyes. When performing in Edinburgh they used hoods. In Capital (Ljubljana, 1991), the spectators were put into a moving box that with each 90 degree turn hid the previous territory and revealed a new one; in the Prayer Machine Noordung (Ljubljana, 1993), the spectators were seated in a comb on stage while the dancers moved among their heads; in the 1:1 (Ljubljana, 1995 – 2045) performance, he introduced an imaginary, wholesome, divine perspective from above.

Ladomir-Φaktypa: Fourth Surface - The Surface Of Contact! (Ljubljana, 1996), a performance by Marko Peljhan in an Italian box, cut into three screens, is in itself a castration machine.

- The directness pictures the Utopia of the poem Ladomir (1917 - 1922) written by Russian poet Velimir Hlebnikov: archaism and ruralism based upon Russian, Ancient Slavic and Asian folklore, the golden age marked by a symbiosis of man and nature, tools and arms, people and animals. At this level, castration symbols are also direct (sickle, scythe, rake, spear, cabbage, cutting, harvesting, threatening animals).

- The mediation is represented by TV screens with an unbearable repetition of castrating "un-montaged" satellite feeds.

- Mediated directness is achieved by means of kinetic diaphragms upon which ads for the military aviation industry and shots of the untouched underwater world are projected. Simultaneously, slides from six projectors are projected upon the movable diaphragms, which with their metaphorical and metonymical mixing and composition of images imitate the structure of dreams – the "royal way to the unconscious."[27] The projection mixes two principles: the self-sufficiency of the underwater life sends the spectator back to the pre-natal safety of the womb, whereas bombers flying over him reinvoke the fatherly threat of castration upon which the introjection of the law of the Name-of-the-Father follows.

In his Four Scenes In A Harsh Life (Santa Monica, 1994) and Deliverance (London, 1995), American artist Ron Athey explores the origins of pain and pleasure using his own body as artistic object. He connects Christian spiritualism with gay and AIDS activism and bears all the stigmata related to the body in the Christian tradition: sexuality, homosexuality, sex change, illness, piercing, tattoos, masquerade. He presents the body as the basic means of exchange in Western culture, driving it towards infinite progress and mutual destruction. In this case, the castration machine does not operate with associations but with a demonstration of castration hidden in excess frankness. Travesty, piercing of the head with needles and blood running out of wounds in the shape of a crown of thorns, piercing of the body, cutting the skin off the back, sewing of the lips, sewing of the skin over male genitalia in the shape of a vagina are all a presentation of a pre-Oedipal polymorphic body which is no longer a body of pleasure but a body of work, oedipized by the remains of symbolization, which are the real itself: castrate yourselves.

Emil Hrvatin's Male Fantasies (Ljubljana, 1997) performance explores the relationship between a patient and a doctor who is in no way hindered by experimenting with a formally non-existent patient. The performance does not produce the cathartic narcissism that would confirm the actor or the spectator in his faith – the trap is his own hidden perverse pleasure: do the most abominable perversions imaginable sexually arouse me? Is the fact that I feel disgust at what is considered sexually attractive somewhere far beyond the moral norms? The performance was - expectedly? - received extremely negatively, especially by the theatre people.

More Analysis of Truth

Lacan's psychoanalysis is not therapeutic in the Freudian sense ‑ it is not about helping the patient enjoy, it is about finding the truth. It is a truth of philosophy, an insight that there is no sexual relation, and that he who has never stepped into the binding symbolic order of absence is not a subject (sujet), a serf.[28]

On the objectives of psychoanalysis, Mladen Dolar writes: "In the sense of such radical distrust towards any kind of new births, psychoanalysis follows historical materialism. Many, among them Theweleit, implicitly hold the fact that psychoanalysis does not offer new paradises (finite unalloyed pleasure, finite liberation from under the burden of bondages and prohibitions), but only a revolutionary alteration of the concrete existing relations, against it."[29]

And on the symbolic, Slavoj Žižek writes: "The deceit implied by the symbolic ‑ which is also one of the classical Lacan's topoi - is more complex, it is deceit by the truth itself: the deceit of telling the truth by counting on it being understood as a lie; such deceit is no longer possible at the level of the imaginary."[30]

Aspiring to the Ever-returning Same

The clinic of a pathological narcissus and of disavowed symbolic castration is based upon the notion of the master, stimulating an analogy with trials for witchcraft in Europe and later in America from the 15th to the 18th centuries, enacted by a papal bull of Pope Innocent VIII.[31] At first, a number of male heretics were convicted, but soon the majority of victims were women of the beggarly, peasant or middle classes. After precisely prescribed torture consisting of atrocities, almost everyone that did not die confessed. Burning at the stake was a punishment for both the repentant and the stubborn, except that the first were burnt dead and the latter alive. The most important device for exerting confessions was a specially devised chair with nails onto which the suspect was screwed. The main conviction concerning female witches was having experienced sexual enjoyment with the devil, having murdered children and used them for the production of an ointment that helped them fly around and meet with the Devil while their husbands were sleeping. Jews were subject to the same conviction – enjoying sex and murdering Christian children. The guilt of homosexuals corresponds to the same crime – enjoying the Devil's sexuality.[32] The incredible pleasure that can only be illustrated by slaughtering innocent children is a common denominator of the intolerant ideologies that we are trying to push away into tales. Witches around the world confessed to the same thing, which was a proof enough of the existence of witchcraft – and they confessed to what was written in the most notorious work on witchcraft of that time, Malleus maleficarum, maleficas et earum[33] written by Institoris and Sprenger in 1486 and reprinted 28 times by the year 1669. Similarly, anybody, anywhere, any time can correspond to the clinic of a pathological narcissus and disavowed symbolic castration. In this case, the machines for symbolic castration have the same role as the chairs used for torturing witches.

In Slovenia, confessions to witchcraft looked like this:

The Process at Poljane, 22nd April 1693

"Question: Do you have a house or a castle at the Klek[34] and how is it there?

Margareta Šmalc: There is a huge rock on the hill, very smooth on the top and very wide. The evil spirit built a large, beautiful castle there with many rooms, beds, windows, kitchens and cellars, where they eat, drink, dance and jump around. After rejoicing, everyone goes to bed with his favorite. If a witch calls Jesus' name or makes the sign of the Cross, everything disappears in an instant.

Question: At the beginning, you mentioned that you needed an ointment to fly, a "masilu". Where and how is this ointment produced or where do you get it?

Margareta Šmalc: We make it at the Klek in the evening on Good Friday. We take butter made of breast milk and the hearts and fat of young children. But the most important ingredient is the host, brought by the women named Rode and Ficl. I also brought the host three times, threw it on the floor among other hosts and stomped on it, beat it with hazel birches so that they shone like the sun. After that revilement this key ingredient was added to the heart and the fat of a young child to produce the ointment. The ointment was later distributed among us."[35]

Self-analysis, Upbringing, Domination

Desire for truth or fear of the species' extinction are not the only elements that run castration machines, which sacrifice people so that the subject - due to feelings of guilt - internalizes the symbolic law by which the subject abides only on the surface of social role playing. Castration machines are also driven on money although with an asserted alibi of scientific research, social benefit, natural truth and benevolence. And, last but not least, castration machines are run by the remains of the real ‑ pleasure and death.

Translated by Mojca Krevel

2. The Rise of the Utopia

[uredi]2.2 Mistake

[uredi]DV8 Physical Theatre: Enter Achilles, choreography by Lloyd Newson[37]

"DV8 Physical Theatre is about taking risks, aesthetically and physically, about breaking down the barriers between dance, theatre and personal politics, and above all, about communicating ideas and feelings with clarity and unpretentiousness. It is determined to be radical yet simultaneously accessible and to take its work to as wide an audience as possible. DV8’s approach aims to reinvest meaning in dance, particularly where it has been lost through formalised techniques. Its work inherently questions the traditional aesthetics and forms which pervade both modern and classical dance, and attempts to push beyond the values they reflect to enable a discussion of wider and more complex issues." (Lloyd Newson)

Among other things, the name DV8 alludes to socially deviant behaviour and to the camera format 8, which its members use in their work that also involves film. DV8 Physical Theatre transfigures movement from its everyday dimension into a choreography of feelings as subtle as the butterfly effect, yet strong enough to disrupt unity, and emotionally kill a relationship between two, three, four … human beings. These are, however, not feelings of great passion, love or hate, but rather, their everyday variations. The cycle between the viewed and the viewer, the slave and the master, reveals itself as a personal relationship. DV8 narrates linear and chaotic stories, conjuring up and analysing human relationships and relations between the sexes with speech, song, symbols, stage set design, costumes and music. It is body language, however, that dominates the aesthetic and cognitive experience. Through the physical dimension, which can be both brutal and sensitive, DV8 touches on the ritual origins of theatre and on its symbolic impact on the crucial prohibitions within a culture. The group voices ordinary and essential questions concerning the relationship between the masculine and the feminine, that bone of contention of contemporary social theory. With Achilles, Newson further radicalises the issues of man's world.

Enter Achilles combines a physical and a theoretical plan. A down-sized pub, which makes the male actors seem taller, is a world of machismo and stories of everyday life. A black-and-white cube placed above the pub represents the world of yearning to transcend everyday life, or even trying to live up to it. The pub is a sanctuary of male playfulness, openness, camaraderie, drinking, fighting, bragging, seduction and vulnerability, which are all attempts to suppress anxieties, fears and tenderness. The medium of communication is the beer mug. Superman, who comes from some other, faraway world, has feminine qualities and unmanly attributes which are the object of mockery. As are the intimate feelings of one of the guys, namely his attachment to Sandy, a plastic sex doll, which is being abused by his friends. The dominant culture covers up its own fetishisms by overtly marginalising fetishist subcultures. Sandy's friend climbs to the top of a three-headed[38] mountain, at the foot of which is an aquarium containing Sandy, the human fish,[39] while a patriotic song floods the entire scene. Individuals try to live with their alienation; they suppress it and become attached to any subject/object they can.

In a male-dominated world, so characteristic of the patriarchal society, women are pushed aside either openly or in more subtle ways. Yet even the most radically oriented of these societies cannot do without them. Women are the essential counter-principle of male domination and universality, in terms of particularity, domesticity and reproduction. The world of men ‑ i.e., a world without women, as opposed to a world of male domination ‑ ceases to be a world of heroes, warriors and victors, and becomes a world of sensibility, much closer to the feminine side; one that is closer to the world of emotions, love, seduction, sacrifice, disappointment; closer to the capacity for self-sacrifice. It assimilates the feminine side through its ability to openly combine opposing qualities, grouped by cultural stereotypes into two polarities of gender: the passionate and the rational, the soft and the hard, the wet and the dry, the unacceptable and the permissible, the gentle and the violent. A world of men without women, as a public world, is bereft of its dominant male position, and turns into a subjugated, vulnerable, marginal world ruled by women.

Virile male bodies come to symbolise weakness and emotional vulnerability, and the world of men now also becomes a world of love between men ‑ the love that can be exactly the same as the love between a man and a woman, unbinding or totally devoted. With such a different world of men, DV8 Physical Theatre problematises the self-evident social structure - the gender difference as the basic common denominator. Disregard for gender difference brings on the trauma of original identity, the envy of non-yearning which equates identity with the psychotic exclusion of the difference to which the technologically oriented society aspires anyway. The world of men without women - which women find even harder to accept because they are neither part of nor excluded from it - feels this unbearable sensation of blurred differences. The more the world of male dominance remains insensitive to the world of men without women, the more it is being taken over by women who are irritated by this lack of interest and who make their lives meaningful by converting such men. The world of men without women has the social function of providing an outlet by not responding to the issue of the masculine and the feminine.

Translated by Judita. M. Dintinjana

2.3 Rise of the Salvational

[uredi]The innovativeness of Vito Taufer springs from his curiosity and a delightful playfulness that allows one's imagination to wander freely enough to essentially contribute to the creation of the stage event. By tackling traditional theatre forms and styles, Taufer creates a language marked by originality and modernity - the qualities that will often shine through upon reflection. Dealing with various aspects of high culture and entertainment, and popularising theatre in the age of virtuality, he remains loyal to the ethic principle. He also excels in his attentiveness towards the actor. On the 370th anniversary of Molière's birth in 1992, Taufer’s initiative brought about the creation of Tartif by Andrej A. Rozman, and that of Psyche[41] by Emil Filipčič. The drama-ballet about the power of love and hate[42] was rendered into the modern world of financial moguls, cynicism and black humour. Taufer blends tragedy with comedy, opera with sport, and the world of gods with that of village entertainers. The lacking qualities become obvious through the conspicuous presence of other traits – the lack of trust through vulgarity, and insufficient emotional intelligence through embellished, Baroque manners. Rozman and Filipčič both depict comedy and tragedy amid the sublime and the vulgar; the most profane of jokes thus reflect the deepest individual tragedy, the inability to control one’s situation. Both deal with the fixation of Slovenian high culture on the art of tragedy, and with the double standards of burgeois culture. Enabling high art, the latter is characterised by the etiquette of freethinking on the one side, and the hidden automated obedience to the ruling institutions on the other.

Andrej Anabaptist Rozman: Tartif, directed by Vito Taufer[43]

In Rozman's Tartif, written in verse, the philosophical mind watches the immediate naivety from behind the scene. The front of obscenities veils tragic traits similar to those of other Slovenian tragedies (e.g. The Baptism at Savica by Dominik Smole[44]).

Orgon is in love with Tartif. This passion drives the mechanisms of domination, upbringing and psychoanalysis. Only the beliefs generated in the state of infatuation can establish the relationship of superiority and inferiority, the transfer of knowledge, and the analytical process. An allegory of the analysant, Orgon is an infatuated paranoid no longer able to differentiate between business and privacy, with his obsession with hygiene reflecting guilty feelings. Tartif, on the other hand, symbolizes a wild analyst who enters relationships – or rather, business deals with others, by appealing to their unfulfilling sexuality and promising delight.

Molière still makes use of the instance of warning - Cleante, albeit with no practical effect. The hypocrisy in Rozman’s drama, however, is only evident to the spectator detached from the love relationship with Tartif. Tartif wins Orgon's trust by enhancing his paranoia - by physically producing its imaginary cause in the form of shit. Ruling the world calls for eternal youth, with the degraded man of the future reflecting the present state. Orgon becomes a trader with the labour force, and hereto pertains Tartif’s witty comment:

"I’d buy and sell them all by parts (…)

Behold the world’s true face:

Those who always seek their gains

Win the survival race."[45]

This is the highest ethic principle. The call for human rights is uttered by a child; the child's right to play, however, signifies that of smearing and maltreating his environment. The antipode of the child, to whom everything is to be allowed, is the sportsman, subjected to constant limitations and analyses. The spirit is in need of the body; it therefore makes it a profitable business to drain the spirit from the sportsman’s body in order to replace it with one’s own. Tartif conceals the truth about himself by openly advocating it. Orgon accepts him as a sexless being, and the transfer becomes immune in its mutations. The omnipresent hypocrisy stands for bourgeois norms carried to extremes by people who pretend not to know things widely known.

Tartuffe is a play about the unconscious, written long before the notion was invented. The situation staged by Molière is an analytical one, a narcissistic confession perverted by realisation. Rozman, however, presents the mechanical manageability of the unconscious as a tragicomic outcome of bringing to life the idea of man-machine, the ideal of the Enlightenment. The wiles of Molière's Elmire unmask Tartuffe; the Elmire of Rozman is hampered by the inability to talk about female pleasure. With Molière's woman having contributed to the end of the psychoanalytical situation, female aid is no longer present in Rozman’s text, enabling the psychoanalysis to turn into an unending process.

A stronghold of democracy, the police protects the democratic order from the totalitarianism of know-it-alls who constantly come up with new disguises. Deus ex machina takes on the form of a police inspector who gasses the building to shield the family from cannibalism and terrorism. In the name of truth, he saves Orgon from ruin, and produces a happy ending. Taufer, however, suppresses Orgon's regained vision; the inspector is Tartif himself, who returns in the form of a hologram. Virtuality, which can be exactly the same as reality, except for the fact that one can never really know, triumphs supreme in the tragic happy ending. In Hitchcock-like manner, the director appears on the TV-phone, showing that the plot can be viewed as a crime story. Funny crime stories, however, are serious business.

Vito Taufer: Silence Silence Silence[46]

The creative team is intrigued by the unconscious hidden behind emotions, thoughts, behaviour and stage acting. Each of the six actors chose their particular mask and their medium of expression. Silence Silence Silence is a Freudian performance. The theatre director - an analyst - enables the actors to articulate their unconscious truth and render it into artistic expression. The visualisation medium is that of body language, entailing the dimensions of both wholeness and separateness. The physical difference between the sexes - the fact that woman is "castrated" – is perceived by the eye before the mind, but during the socialisation process, both sexes are symbolically castrated, as they are both incomplete.[47]

Based on six individual renderings, Silence Silence Silence is a mythological narration about the creation of the world. The unconscious is governed by laws as methodical as those of mathematical axioms. Aluminium, polyester, styropore and makeup are used as the building blocks of the world: earth, fire, water and air, completed by the combining and dividing force. Offered the basic theatrical glossary, the spectator contemplates illusion and reality.

The mask of Janja Majzelj are the eyes, bulging, but with limited vision. Wrapped into the shimmer of aluminium foil, she attracts the gaze which in itself symbolises an object of desire. The missing object is replaced by voice, making her complete within mythology. She becomes Gaia, the Earth, created out of chaos, out of the dark and indistinct abyss, the one who brings forth from her own wholeness Uranus, the Sky, and thus generates the Cosmos which sets all the differences in order.

The shrouded head of Janez Škof, the Sky, symbolises creation. With articulate movements, he descends on the Earth, with whom he unites. Born of this union - for incest is not forbidden to the gods - are Titans. Four brothers marry their sisters; among them are Chronos and Rea, the fore-parents of Olympic gods.

Ravil and Nataša Sultanov, a male-female couple, are doomed to longing and fear. The female, confined in a ballet box, is a mask of the male. The chest contains hope at its bottom, but it closes up before hope has the chance to escape to where people exist, and where all the troubles, ailments and pains have already fled. Chronos has castrated his father Uranus with a sickle, saved his brothers and seized power. Fearing the same fate, he devours all of his children, but Rea replaces Zeus with a pebble. Zeus defeats Chronos and saves his brothers. He keeps the sky for himself, and gives Hades the underground.

Uroš Maček, Hades, wears his own death-mask. He builds the wall of time, separating eternity from events. The underworld is the time of silence, and that of the staged gaze.

The mask of Robert Prebil is the letter A, drawn onto his face. With the force of his entire body, he tries to articulate a phoneme, engendering screams, thunder and lightning that crush the stone. The creation of the new world destroys the former. Zeus is the avenger to his Ancestor and, at the same time, the ancestor of a new line of gods. The crisis of the language reflects that of the sexes.

Afterwards, Prometheus made man out of clay, gave him the gift of reason and led him into the struggle against god. "The danger is this salvational, inasmuch as danger, by its stealthily transmuting essence, generates this salvational."[48]

III. Jana Pavlič: The Nineties Transformers

[uredi]The Cadastre of the Creators of the Contemporary

[uredi]The cadastre of the creators of the contemporary Slovenian theatrical territory of the nineties

A cadastre (< nLat. catastrum Lat.capitastrum) is a register of a country’s land property, the basic list where all its land is to be recorded. The creators of the contemporary Slovenian theatrical territory thus symbolize the composing parts of the land, autonomous plots that do not form a uniform theatrical system, but a wide front of theatrical artistic forms.

The nineteen nineties have given rise to numerous types of small autonomous units dedicated to modern creation, caught in the whirl of production and distribution battles. This cadastre is a humble attempt to record the searchers for the new - the transformers (< Lat. transformare = to make a through or dramatic change in the form, outward appearance, character, etc.) of theatre, who have made the last ten years a bit less boring.

Matjaž Berger

[uredi]Born 1964. He graduated from dramaturgy, and theatre and radio direction (AGRFT, Ljubljana). In 1991, he founded the »School for Theatre Critique«, which later became known as the »Department of Spectacular Arts«. In the scope of this artistic society, Berger created unusual spectacles that contain elements of demanding sports disciplines (alpinism) and thus settle the real topos, transmuting it into the space of the sublime. Defining theatre as »spectacular arts«, Berger approaches it through theoretical analysis connected with sports, anthropology, and the state. He perceives theatre as a phenomenon, advancing it further by means of his individualist stage praxis – the interpretation of classic texts and theoretical discourse, transforming his outgoing bases into entirely different texts.

Major works:

- Directions in the scope of the “School of Theatre Critique” and the “Department of Spectacular Arts”:

Sports:

- Paris – Amsterdam – Berlin – Novo mesto, celebration of 95th birthday of Olympic champion Leon Štukelj, 1993

- Nomads of Beauty, opening ceremony of Giro d'Italia, 1994

- The Three Final Problems of the Spirit, opening ceremony of European Triathlon Championship, 1994

- Mass 116, opening ceremony of Slovenian Sport Parachute Competition, 1994

Anthropology:

- Norge, 250th anniversary of the old Novo mesto high school, 1993

- Volunteers on Mt. Eiger, the climbing wall and the iron bridge in Novo mesto, 1993

- Spirit is Bone I, Pleterje monastery, 1994

- The Three Final Problems of the Body, Cerov log quarry, 1994

After the abolition of the two institutions, the following directions have taken place:

State:

- Triumph, 50th anniversary of victory over fascism, 1995

- Kons 5, 5th anniversary of independence of the Republic of Slovenia, 1995

Anthropology:

- Spirit is Bone, 250th anniversary of Novo mesto high school, 1994

- Rotation of the Cosmos 100 - opening ceremony of restored Ljubljana Power Station, 1997

- Guardian of Interpretation, hommage to constructions, Novo mesto, 1997

- Around the Forbidden Book, artistic action at the opening of Nova Gorica Library

Sports:

- Ave, triumphator! – centenary of Olympic champion Leon Štukelj, Novo mesto, 1995

- Farewell to Evald Rusjan, old stone bridge in Solkan

Theatre:

- Bertolt Brecht: Galileo Galilei, Mladinsko Theatre and National University Library, Ljubljana, 1996

- W. Shakespeare, F. Nietzche, J. Lacan: You Never See Me Where I See You,

- Mladinsko Theatre, the riding hall of the agricultural school Grm, Novo mesto, 1997

- W. Shakespeare: The Voice (Richard II, Henry V, Richard III), Mladinsko Theatre, 1999

- S. Freud: Die Traumdeutung, co-produced by Mladinsko Theatre, Postojnska jama, turizem d.d., Slovenian Television, 2000

Niko Goršič

[uredi]Born 1943. He graduated in dramatic acting (AGRFT, Ljubljana). As an actor, he has co-operated with numerous directors and theatres. He began his theatre direction research in the mid-nineties under the pseudonym of Nick Upper. He defines himself as “situated within postmodernist aesthetics, and enforcing global theatre of touch – the artistic form comprising all elements of theatrical art: the dramatic text, movement, music, visuality, dramaturgical and acting puzzle techniques, direction and the audience”. In acting pairs, Goršič has been challenged by marginal themes - twisted eroticism arising from the classic form of marriage between man and woman, the travesty of body and soul, and man-woman and woman-man captured by the civilisational determinism of a person’s sex.

Major works:

- E. Filipčič: The Puzzle Home, Mladinsko Theatre (Open Mladinsko), 1996

- B. - M. Koltes: In the Loneliness of the Cotton Fields, Mladinsko Theatre (Open Mladinsko), 1998

- G. Polajnar, N. Upper: Kill! I Don’t Love You, 1999

- L. Djurković: The Puppet House/Tobelija, Ex ponto, Ljubljana, Montenegrin National Theatre Podgorica, Montenegro, 2000

Sebastijan Horvat

[uredi]Born 1971 in Maribor. He studied theatre and radio direction (AGRFT, Ljubljana). He founded the independent structure E.P.I. Centre, which enables him to produce his research projects. He is especially interested in verbal and drama theatres, regarding the text as a privileged element of the actor’s manipulation and the instrument of his virtuosity – especially that of his voice. The voice establishes the dualism of the body – tangible material bound to reality and the field of gravity, and the non-material, pure vibration, generated by the body in the form of the voice. Horvat’s performances employ the actor as the body listening to its non-material voice and interact with it, giving rise to vocal atmospheres – the new garments into which the text is clad.

Major works:

- F. M. Dostoevsky: The Karamazov Brothers (theatrical adaptation of the novel), a drama and music project, AGRFT studio and Slovenian National Theatre Drama Ljubljana, 1993

- Aeschylos: The Libation Bearers (the second part of the Oresteia trilogy), Ohrid Summer Festival, Macedonia, 1993

- Elsinor (based on Hamlet by William Shakespeare), graduation performance, AGRFT, 1994

- F. Wedekind: Spring Awakening, Municipal Theatre Ljubljana, 1994

- E. Ionesco: The Lesson

- Glass – Echo, 1995

- Elizabeth, Ptuj Theatre, 1997

- S. Belbel: Caresses, Slovenian National Theatre Drama Ljubljana, 1997

- Camus: Caligula, Municipal Theatre Ljubljana, 1997

- G. Stefanovski: Bacchanalia, Primorsko Drama Theatre Nova Gorica and AGRFT, 1998

- ION, E.P.I.Centre and Slovenian National Theatre Drama Ljubljana, 1998

- B. - M. Koltès: Roberto Zucco, Sliven teater, Bulgaria, 1998

- E. Ionesco: Makbet, Slovenian National Theatre Drama Maribor, 1998

- M. de Sade: Juliette Justine, E.P.I. Centre and Mladinsko Theatre (Open Mladinsko), 2000

- SS/Sharpen Your Senses, Glej Theatre, 2000

- A. de Musset: Lorenzaccio, Slovenian National Theatre Drama Ljubljana

Emil Hrvatin